Few livestock parasites are as horrifying as the screwworm. Why? This parasitic flesh-eating worm, scientifically known as Cochliomyia Hominivorax, targets warm-blooded animals, including cattle, goats, sheep, and even humans. Unlike typical pests, the screwworm’s larvae burrow into open wounds and feed on the living tissue of their host, often causing severe infections, mutilation, and even death if not treated early.

Though it may sound like something from a horror film, the screwworm is a real threat. It is one of the most damaging agricultural pests in history and a nightmare for farmers everywhere.

Originating in the Americas, this pest formerly afflicted areas ranging from Argentina to the southern United States. Decades of intense eradication campaigns helped eliminate it from many regions, but troubling signs suggest a possible comeback.

Several factors contribute to its re-emergence: climate change is altering ecosystems and creating favourable conditions for the pest to thrive; the growing international livestock trade increases the risk of cross-border spread; and the weak surveillance systems make early detection harder, especially in countries with limited veterinary infrastructure. If left unchecked, a screwworm outbreak might seriously harm livestock sectors, particularly in underdeveloped countries with little access to veterinary care.

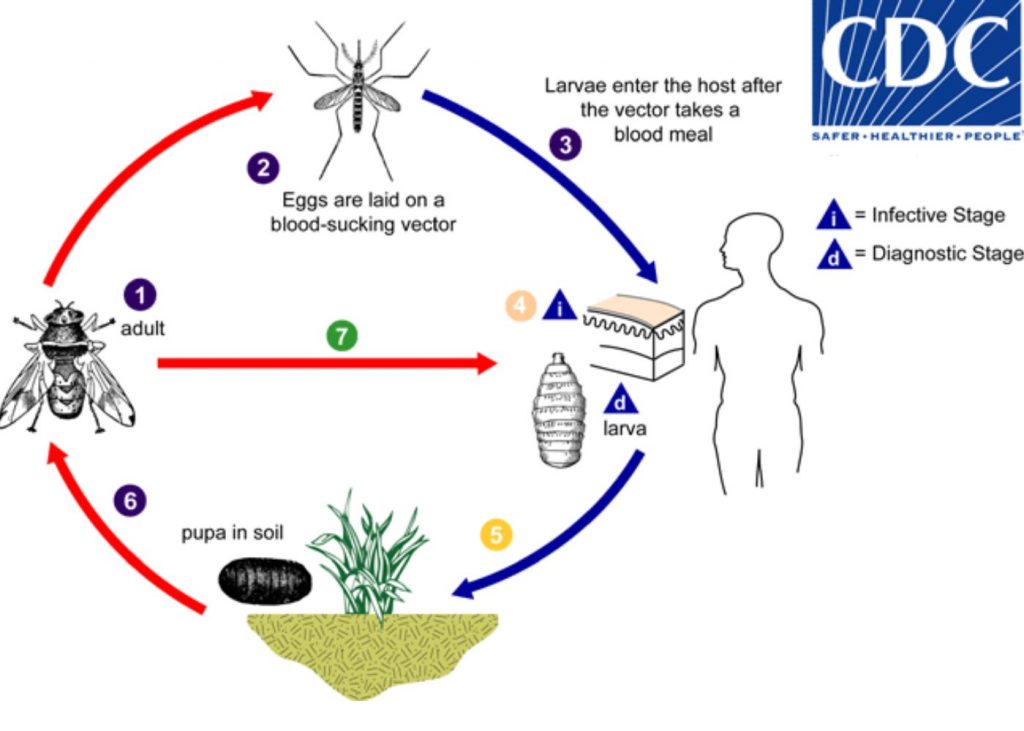

The screwworm’s unusual life cycle makes it particularly deadly. Female flies deposit their eggs on exposed wounds, such as little scratches, bug bites, or the navels of young animals. The eggs develop into larvae in a matter of hours, and as they spiral inward like a corkscrew, they feed and grow while boring into the flesh.

After five to seven days of this feeding spree, the larvae fall to the ground to pupate. Adult flies emerge in warm areas within a week, prepared to continue the cycle. Hundreds of larvae can eat a single animal alive when dozens of females are drawn to an untreated wound.

Screwworms consume living tissue, unlike other fly larvae that consume decomposing materials. The larvae twist and burrow further, destroying tissue and inflicting excruciating pain. This horrifying procedure justifies the flesh-eating worm’s name and how quickly it spreads. Animals suffer from extreme psychological stress in addition to physical pain, which can occasionally lead to the affected livestock ceasing to feed or withdrawing from society.

How to identify Screwworm infestation in Livestock

A screwworm infestation can cause severe tissue damage, secondary illnesses, and even death if it is not detected in time.

Despite being eradicated from the US and other areas of Central America, screwworms are still an issue in places like South America (particularly Brazil), the Caribbean and Parts of Asia and Africa.

A startling screwworm outbreak in Florida’s Key Deer population in 2016 raised concerns about its possible reintroduction into the country’s livestock industry. More nations might be at risk than previously believed due to rising temperatures and increased animal mobility.

The fight against screwworm infestations is a global effort led by several international organisations. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) play major roles in eradication campaigns and emergency responses across affected regions.

One of the most effective and widely adopted control methods is the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT), pioneered by the FAO. This method involves the mass breeding and release of sterile male screwworm flies. When these sterile males mate with wild females, no offspring are produced, causing the population to decline over time without chemicals.

Beyond SIT, governments and agricultural agencies have strengthened their efforts through:

While progress has been made in eradicating screwworm in several countries, sustained investment and coordination are critical to prevent the pest from re-emerging and spreading to new regions.

The resurgence of screwworms presents a serious and growing threat not just to livestock but also to global food security, rural economies, and public health. These flesh-eating parasites, known for burrowing into the wounds of warm-blooded animals, can infest pets and even humans, especially in tropical and subtropical regions. A localised outbreak can quickly escalate into a global crisis in our interconnected world.

The risk of wider outbreaks is heightened in today’s climate, where global temperatures are rising and animal transportation is more frequent. Investing in sustainable, science-backed pest management strategies, early detection systems, and stronger veterinary infrastructure is essential. Farmers and rural communities are often the first affected, and they need targeted support, public awareness, and training to identify and respond to infestations quickly.

Addressing the threat of screwworms is not just a veterinary concern but a food security, economic, and public health imperative. As stewards of agricultural resilience and biodiversity, governments, researchers, and stakeholders must cooperate to prevent the spread of this parasitic menace.